掲示板 Forums - Some Doubts again..

Top > 日本語を勉強しましょう / Let's study Japanese! > Anything About Japanese Getting the posts

Top > 日本語を勉強しましょう / Let's study Japanese! > Anything About Japanese

1. Is that how can a kanji can have this much reading?! Even though it is not to be studied, but why was it studied?

2. What is the difference between the me and ma like 集める and 集まる. I also see verb forms ending in -れる, what does it differ from the normal ending ru?

3. When I do grammar questions in renshuu based on the ~kudasai, I see questions like :

-> 立ってください/立って下さい

-> この椅子にすわないでください/この椅子にすわないで下さい。

Why is there the necessity of using the kanji in some questions and not in some??

I’m not super knowledgeable but I believe that the difference between the まる and the める is that the まる is intransitive and the める is transitive. Meaning that with the transitive verb, someone is doing something to something else, whereas with the intransitive something is doing something to itself. I think the inconsistencies with the kanji and not kanji of ください may be simply based on formality. I’m not completely sure and I very well could be wrong so someone please correct me, but I hope I could be of service to you.

ありがとうございます!

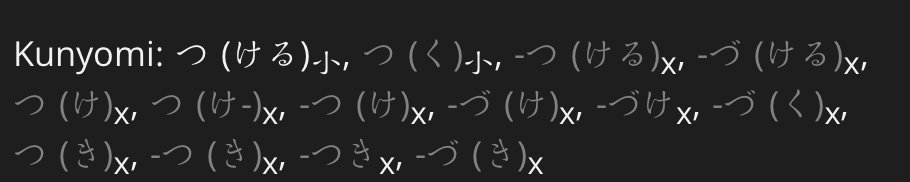

1) It's essentially the same reading though, isn't it? It's the root つ_ with is inflections and its 連濁 form. You're not really supposed to learn them all by heart, I'd say.

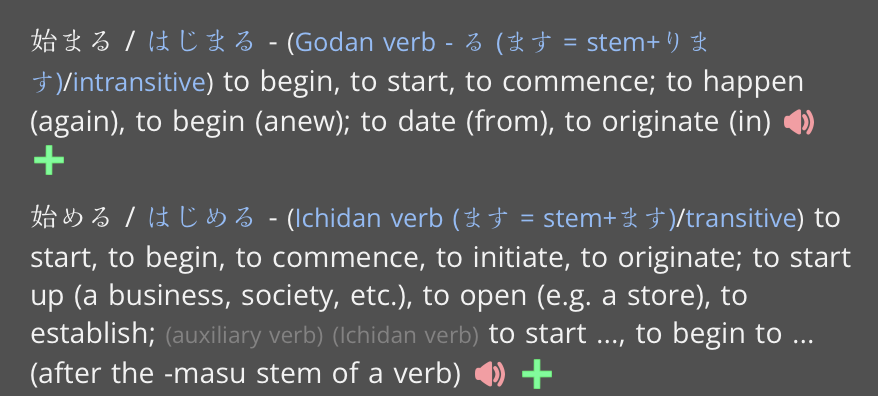

2) 希空(ノア) is right, the simple explanation is something like transitive/intransitive. If we read through the whole definition with all the details, we can see that 始まる means "for something to begin", while 始める means "for you to begin something". It's not always this straightforward, but it works as a rule of thumb.

As for -れる, 、-させる and so on, they're all verb inflections. You can find a lot of information and lessons/detailed explanations/convo threads on them by looking up any verb in the dictionary, tapping above the definition where it says, for example, (Godan verb - る (ます = stem+ります)/intransitive), and see the whole list - casual, invitational, volitional, causative etc.

3) Maybe more experienced learners can help us with this. What I've guessed so far is that it's a matter of the level of formality, sometimes the nuance, and... personal preference, maybe?

In theory, every Japanese word has its kanji, even する and いる, but some are so usual that people have stopped using it (I may be missing important information here, this is just my grasp of it as a beginner). On the other hand, I remember reading some Bleach manga and seeing Rukia (who acted very formally in the first arc) with speech bubbles that used kanji for almost every word.

I've also seen "us", for example, written as both 私たち and 私達 in sentence examples in Renshuu, or even on the same page of a book. I've been meaning to post on the forums and ask, but I kept hoping I'd figure it out on my own or understand it from googling...

no luck yet.

Then there's the separate situation of nouns that can be written with different kanji to express slightly different things, or verbs that are written with kanji when used in the literal sense (来る, 見る) and with hiragana when they have a non-literal or auxiliary meaning (落ちてくる, やってみる). But that's already something I know very little about.

A bit on the third point. この椅子にすわないでください is more natural. I'd also use the standard form すわらない so it doesn't look like 吸わない.

この椅子に座らないでください。is how I'd write it myself. It's a request to DO something, so kana.

ください (kana) - Used when politely asking someone to do something

下さい (kanji) - Used when requesting or receiving something

(Sources: short, long (I didn't read the whole thing)

私たち vs 私達 is more of a stylistic choice, but I'm not 100% sure either.

There's also situations where you need to use kana for nuance. Both なんか and なにか are written as 何か in kanji. If I want なんか, it has to be kana.